Market Opinion: The U.S. Housing Shortage

America’s housing shortage has been a focal point of much of our political, economic and cultural discourse since the Great Recession (2007-2009). The simple fact is that the U.S. has not built enough housing—single-family or multifamily—to keep up with population growth. This situation was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, and is also a key contributor to inflation, as well as the impetus for recent attempts to expand rent control laws.

The shifting landscape of housing in America has far-reaching implications for commercial real estate (CRE), and very direct impacts on multifamily real estate. This piece provides a brief history of how we got to the current housing situation, and lays out the ongoing consequences for multifamily.

Subscribe now for more CONTI insights

America’s housing shortage has been a focal point of much of our political, economic and cultural discourse since the Great Recession (2007-2009). The simple fact is that the U.S. has not built enough housing—single-family or multifamily—to keep up with population growth. This situation was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, and is also a key contributor to inflation, as well as the impetus for recent attempts to expand rent control laws.

The shifting landscape of housing in America has far-reaching implications for commercial real estate (CRE), and very direct impacts on multifamily real estate. This piece provides a brief history of how we got to the current housing situation, and lays out the ongoing consequences for multifamily.

Subscribe now for more CONTI insights

The Housing Shortage Stemming from the Great Recession

A pervasive cultural theme in America has long been the ambition of homeownership1, but we now face the reality that an increasing segment of the population simply can’t buy a home because the roadblocks are too great.

The idea of an “ownership society” dates back to the 1970s. When the government adopted a less active role in managing the economy, deregulating the housing finance system became a government strategy for balancing laissez-faire economics with meeting the economic needs of voters2. The idea was to unleash the financial markets in order to backfill the role of government in boosting household wealth. In the early-to-mid-2000s, this concept evolved into the centerpiece of the George W. Bush Administration’s domestic policy. At the time, U.S. housing policy was geared towards expanding homeownership by loosening mortgage lending standards3. Developers were eager to capitalize on the push for homeownership, leading to a boom in single-family housing construction.

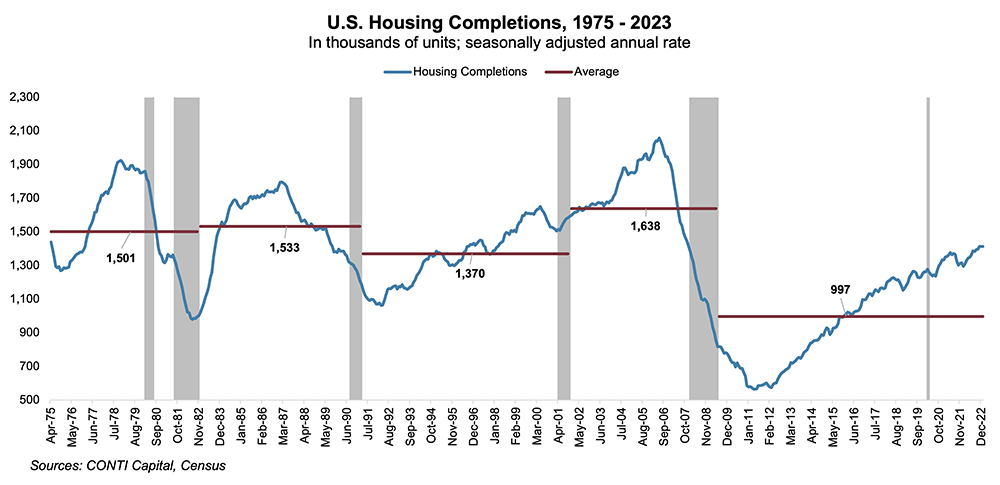

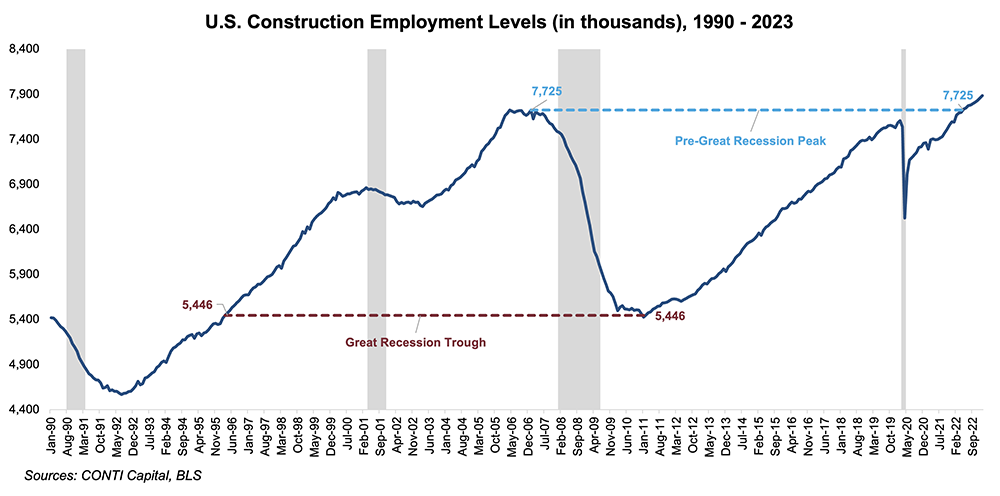

When the housing bubble burst in 2008, developers took heavy financial losses and millions of skilled construction workers were pushed out of the industry entirely. By January 2011, the level of construction employment fell to where it was as far back as March 1996, despite 15 years of economic and population growth.

As the U.S. economy recovered from the Great Recession, demand for housing re-accelerated due to job growth and the entrance of the colossal Millennial generation (born 1981 to 1996) into the housing market. However, the lack of construction workers and developers’ new cautious approach to homebuilding put a damper on residential construction levels. Construction employment didn’t return to its pre-recession peak until May 2022.

The Housing Shortage Stemming from the COVID-19 Pandemic

When the COVID-19 pandemic swept the country, upending the economy, it exacerbated preexisting trends within the housing market. The pandemic catalyzed social distancing measures and caused a sudden uptick in remote work, which made it much easier for office-based workers to move further away from urban centers and spread out into the suburbs. Government intervention in the form of several rounds of fiscal stimulus, interest rate cuts and quantitative easing padded household bank accounts, giving households a leg up on homebuying. But because housing supply continued to lag supercharged demand, home price growth began to ramp up drastically. In fact, recent research has shown that remote work by itself pushed home prices up by 15.1% between December 2019 and November 20214.

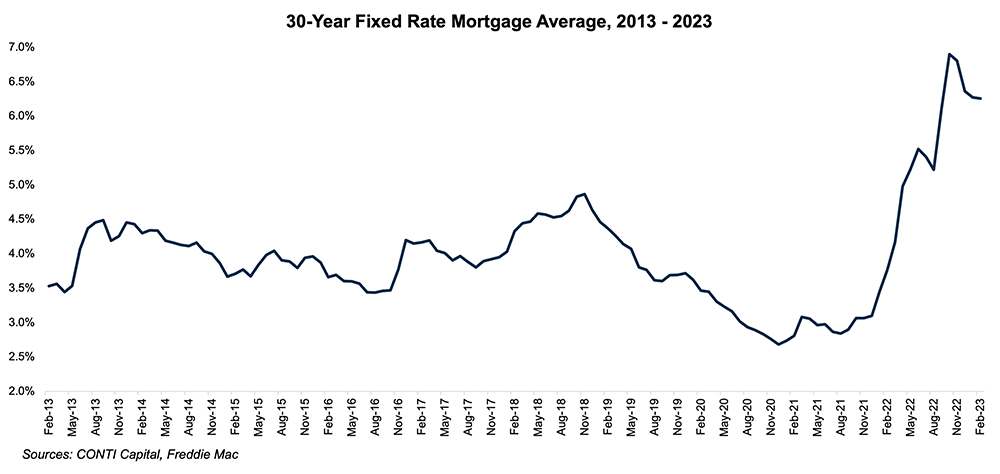

Beyond the impact of remote work, ultra-low mortgage rates played an important role in the current housing shortage. In the face of the Great Recession, the Fed dropped interest rates to zero, where they remained until 2015. After a brief attempt at interest rate “normalization”, the pandemic pushed the Fed to cut interest rates back to zero. The impact on mortgage rates was striking: a 30-year fixed mortgage fell as low as 2.65% in 2021, creating a strong financial incentive for households to jump into the homebuying market. Thus began a much more rapid rise in home prices.

Inflation and the Housing Shortage

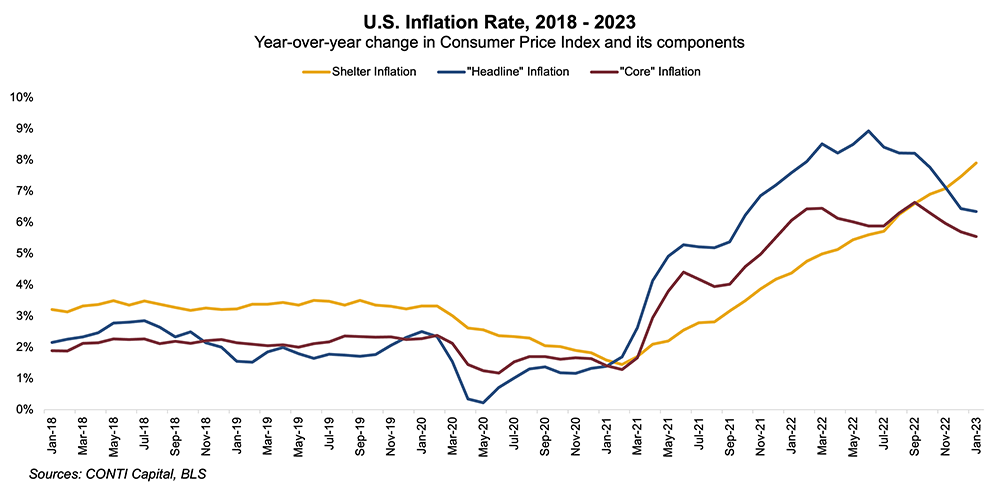

The housing shortage and resulting climb in home prices were major factors in the inflation that enveloped the economy in 2021 and 2022. Shelter costs represent about a third of the Consumer Price Index, meaning that any significant change in housing costs will have a pronounced impact on overall inflation.

In response to rising inflation, the Federal Reserve began raising interest rates in an effort to cool the economy beginning in March of 2022. As expected, this caused mortgage rates to increase, rising as high as 7.1% in late 2022. This had the overall effect of reducing single-family home sales and bringing home prices down moderately, but overall, higher mortgages compounded affordability issues.

The Give and Take of Supply and Cost

As home prices accelerated dramatically at the end of 2021 and into early 2022, first-time homebuyers found themselves facing historically high home prices and mortgage payments that were costlier than average rent payments. To top it off, existing homeowners became more reticent to sell their homes5. Homeowners who are locked into a lower mortgage rate now don’t have much financial incentive to sell, leading to lower churn in the housing market and further exacerbating the housing shortage.

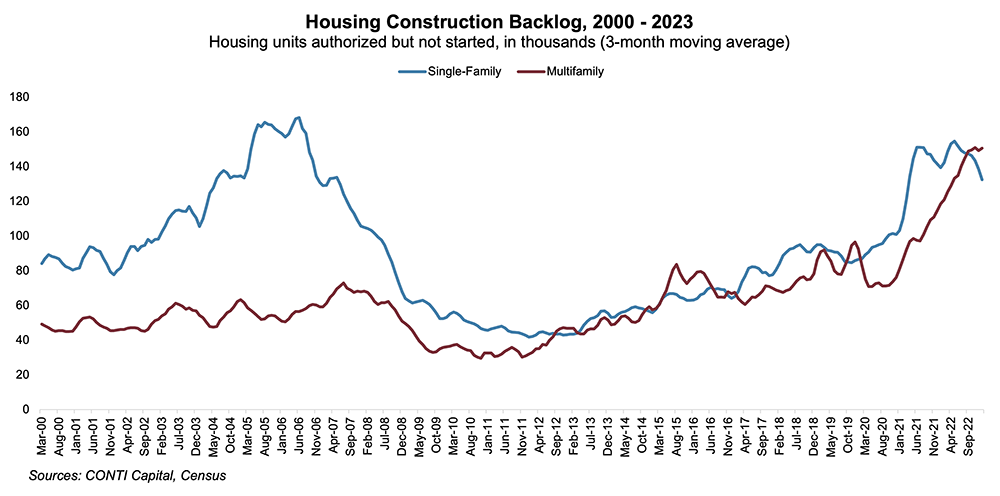

Meanwhile, a rise in prices would typically have resulted in more homes being built, but the response to the price increase in 2020 was muted, largely hampered by pandemic-related supply chain delays6. As a result, the number of housing units authorized for construction but not yet started grew substantially. This is one reason permitting levels may not be an ideal predictor of future completions, since many of these permitted units will likely never be built.

The current housing climate is unusual because, while home prices and sales have moderated in recent months, this is not a sign of deteriorating demand for single-family housing, but an indicator of household financial constraints. While home prices have increased along with inflation more broadly, wage growth has not kept pace.

Ripple Effects to the Rental Market

Thus far we have spoken almost exclusively about the role of the single-family ownership market on the housing shortage because single-family is a substitute for (or a competitor to) multifamily housing. While the apartment market may not be as severely undersupplied as the single-family market, the national housing shortage has direct implications for multifamily.

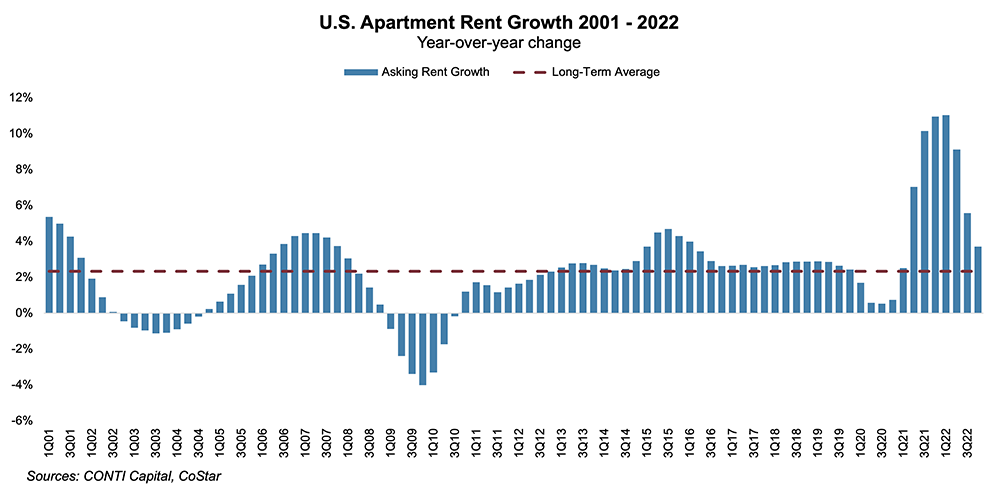

So long as the cost of ownership remains prohibitively high, millions of would-be homebuyers will remain in the rentership market. The crux of the situation for multifamily is that rising homebuying costs are helping to sustain multifamily demand, even amid the current economic uncertainty. This reality partially explains the eye-popping rent growth that occurred in 2021.

For households that might have hoped to buy a home and now find they can’t afford it, there exists a wide swath of rental options to meet their preferences. The apartment industry has evolved in recent decades to accommodate a variety of lifestyles and stages of life. Single-family rentals (SFRs), both standalone and within build-to-rent communities, are plentiful within many major markets. These options provide households with more privacy and space, but without the financial commitment and maintenance costs of buying a home.

Households can also choose from a growing selection of Class A, top-of-market apartments. These assets generally boast new appliances, modern finishes and desirable locations, along with a selection of amenities. That’s why CONTI Capital monitors a wider age range than is typical within our “prime renter” demographic subset – being a renter is no longer so closely tied with being young, low income and single as it was a couple decades ago.

A Note on Rent Control

The continuing shortage and high cost of housing, both owned and rented, is reinvigorating calls for rent control7. While we are sympathetic to those facing rising housing costs, we are mindful of the academic research on this topic, the findings of which are generally unambiguous. For example, a frequently cited study published in the journal American Economic Review tracked individuals in neighborhoods in San Francisco following the implementation of a 1994 rent control measure. The study found that the rent control law was associated with a 15% reduction in housing supply and a significant increase in rents—effectively nullifying the very purpose of the measure.

We have consistently been supportive of those calling for more housing production, not less, as we fundamentally believe that a balanced housing market is key to long-term economic health and multifamily performance.

The Bottom Line

It’s no surprise that rent growth is moderating from the breakneck pace experienced in 2021 and early 2022, since double-digit growth was unsustainable. Behind this exceptional increase in rental rates was the inescapable fact that housing needs are largely unmet in the U.S., and the housing market as a whole is generally unbalanced.

While general economic uncertainty is playing a role in the recent slowing of apartment fundamentals, the housing shortage continues to generate demand for multifamily above what we would expect. The lack of adequate housing supply makes it improbable that we will see below-average rent growth or occupancy rates in the next few years, and we forecast the ongoing housing shortage is unlikely to abate soon. Big picture, people need places to live, and multifamily is well situated to meet that need, thus positioning this CRE sector for growth.

SOURCES

1 “The Homeownership Rate and Housing Finance Policy,” Joint Center for Housing Studies

2 Fernandez, R., & Aalbers, M. B. (2017). Housing and capital in the twenty-first century: realigning housing studies and political economy. Housing, Theory and Society, 34(2), 151-158.

3 https://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/21/business/worldbusiness/21iht-admin.4.18853088.html

4 Mondragon, J. A., & Wieland, J. (2022). Housing demand and remote work (No. w30041). National Bureau of Economic Research.

5 National Association of Realtors

6 Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas

7 Wealth Management, “After a Year of Rapid Rental Hikes, Support for Rent Controls Increased”

8 Diamond, R., McQuade, T., & Qian, F. (2019). The effects of rent control expansion on tenants, landlords, and inequality: Evidence from San Francisco. American Economic Review, 109(9), 3365-3394.